A

brief introduction to Traditional Chinese Classical Music

- The

differences and common ground between Classical (literati) and Folk

traditions from a Historical Perspective

- Liu

Fang

|

This

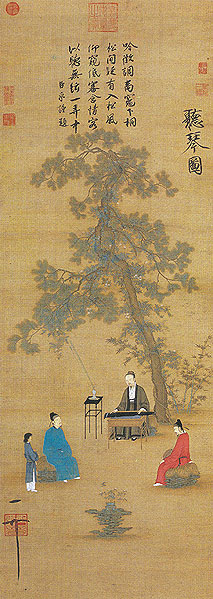

is a famous painting "Listen to the Qin" by the Emperor Huizong

(1082~1135)of the Song Dynasty, one of the greatest artists

in Chinese history.

|

Generally speaking, there are two kinds of music traditions

– classical and folk. Music from the “classical tradition”

refers to art music or “sophisticated” music composed

by scholars and literati in China’s historical past. Chinese

classical music often has thematic, poetic or philosophical associations and is typically

played solo, on instruments such as the qin

(commonly known as guqin), 7-string zither with over 3000 years of

well-documented history, or the pipa,

a lute with over 2000 years of history. Traditional music in the classical

sense is intimately linked to poetry and to various forms of lyric

drama, and is more or less poetry without words. In the same manner

as poetry, music sets out to express human feelings, soothe suffering

and bring spiritual elevation. The instruments demand not only a mastery

of technique but a high degree of sensitivity (and inner power) to

evoke the subtle sonorities and deep emotional expression that rely

very much on the left hand techniques (such as sliding, bending, pushing

or crossing of the strings to produce typical singing effects and

extreme dynamic ranges), where synchronized ensemble playing is virtually

impossible without losing certain subtlety. This type of music has

come down to us as an oral tradition from masters to students, although

written scores that combine numbers and symbols representing pitch

and finger techniques respectively have been in use for nearly two

thousand years. For instance, the earliest scores for guqin we still

have today were from the third century. However it is almost impossible

to play directly from the score without first having learnt from a

master.

often has thematic, poetic or philosophical associations and is typically

played solo, on instruments such as the qin

(commonly known as guqin), 7-string zither with over 3000 years of

well-documented history, or the pipa,

a lute with over 2000 years of history. Traditional music in the classical

sense is intimately linked to poetry and to various forms of lyric

drama, and is more or less poetry without words. In the same manner

as poetry, music sets out to express human feelings, soothe suffering

and bring spiritual elevation. The instruments demand not only a mastery

of technique but a high degree of sensitivity (and inner power) to

evoke the subtle sonorities and deep emotional expression that rely

very much on the left hand techniques (such as sliding, bending, pushing

or crossing of the strings to produce typical singing effects and

extreme dynamic ranges), where synchronized ensemble playing is virtually

impossible without losing certain subtlety. This type of music has

come down to us as an oral tradition from masters to students, although

written scores that combine numbers and symbols representing pitch

and finger techniques respectively have been in use for nearly two

thousand years. For instance, the earliest scores for guqin we still

have today were from the third century. However it is almost impossible

to play directly from the score without first having learnt from a

master.

In traditional China, most well–educated people and monks

could play classical music as a means of self-cultivation, meditation,

mind purification and spiritual elevation, union with nature, identification

with the values of past sages, and communication with divine beings

or with friends and lovers. They would never perform in public,

or for commercial purposes, as they would never allow themselves

to be called “professional musicians”. This was in part

to keep a distance from the entertainment industry where performing

artists used to be among the lowest in social status .

In fact, masters of classical music had their own profession as

scholars and officers, and would consider it shameful if they had

to make a living from music. They played music for themselves, or

for their friends and students, and they discovered friends or even

lovers through music appreciation (there are plenty of romantic

stories about music in Chinese literature). Up to the beginning

of the twentieth century, classical music had always belonged to

elite society and it was not popular among ordinary people. Today

it is really for everybody who enjoys it, and professional musicians

playing Chinese classical music are as common as elsewhere in the

world. However, it is still rare to hear classical music in concert

halls due to the influence of the so-called “Cultural Revolution”

(1966-1976), when all classical music was deemed to be “bourgeois”

and outlawed, and the spiritual side of traditional arts was "washed

out" through the "revolutionary" ideology

.

In fact, masters of classical music had their own profession as

scholars and officers, and would consider it shameful if they had

to make a living from music. They played music for themselves, or

for their friends and students, and they discovered friends or even

lovers through music appreciation (there are plenty of romantic

stories about music in Chinese literature). Up to the beginning

of the twentieth century, classical music had always belonged to

elite society and it was not popular among ordinary people. Today

it is really for everybody who enjoys it, and professional musicians

playing Chinese classical music are as common as elsewhere in the

world. However, it is still rare to hear classical music in concert

halls due to the influence of the so-called “Cultural Revolution”

(1966-1976), when all classical music was deemed to be “bourgeois”

and outlawed, and the spiritual side of traditional arts was "washed

out" through the "revolutionary" ideology .

As well, the influence of modern pop culture since the 1980s has

had a negative impact on the popularity of classical music performances. .

As well, the influence of modern pop culture since the 1980s has

had a negative impact on the popularity of classical music performances.

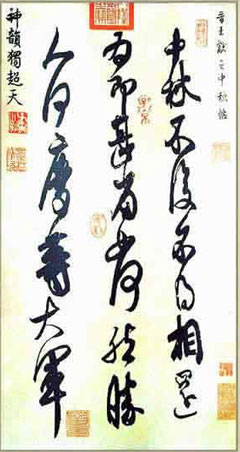

The

above is a painting from the "Five Dynasty" (907-960 AD)

depicting pipa playing

While the classical tradition was more associated with

elite society throughout Chinese history, the resources for folk traditions

are many and varied. Apart from the Han Chinese, there are many ethnic

minorities living in every corner of China, each with their own traditional

folk music. Unlike classical music, folk traditions are often vocal

(such as love songs and story telling etc), or for instrumental ensembles

(such as the “silk and bamboo” ensembles, and music for

folk dances, and regional operas). The various folk melodies have

become a major source of inspiration for the growing repertoire of

contemporary music. In fact, in many contemporary compositions, existing

folk melodies were simply modified, enriched (creatively through advanced

playing techniques and the use of harmonies), and extended. Some were

transcribed so successfully that they may be regarded as an important

part of the growing classical repertoire; for instance the famous

"Dance

of Yi People" composed by Wang Hui-Ran for solo pipa. The

repertoire is further extended by pieces composed or arranged for

multi-instrument ensembles. Needless to say, most contemporary works

are quite Westernized, particularly those for ensembles and orchestras

(modelled on orchestras in the West), which are easily accessible

to the general public, yet veer further away from the classical traditions

. Quite often some of the traditional classical masterpieces are presented

in commercially-packaged shows to look and sound “modern”,

which often gives a wrong impression to listeners who never really

knew the original flavor of the music, particularly the spiritual

side of the classical tradition.

With all that said, there are still a growing

number of performers and listeners who have begun to seriously rethink

the spiritual side of the classical tradition, such that there seems

to be a revival of traditional culture as part of a growing interest

in Chinese classical philosophy, literature, traditional medicine,

calligraphy, painting, Taiji and Qigong.

On the one hand, it goes without saying that

some of today’s excellent creations will become tomorrow’s

traditions (and faked arts will soon be forgotten); on the other hand,

it requires a true master to deliver the vast spiritual and the profound

meaning (inner-feeling) of the masterpieces from the traditional classical

repertoire in such a way as to touch the souls of the listeners, and

indeed, great masters from various musical traditions all over the

world have never failed to support the famous statement: “Authentic

traditional music remains forever contemporary”.

[Note

from Liu Fang]: The above

text was prepared for the lecture

& demonstration at the Julliard School on November 19, 2008

in New York and for several interviews (newspapers and radio).

Special thanks Dr. Annette Sanger (ethnomusicologist and professor

at the University of Toronto) for proof reading and improving

English.

Notes

to the above text

Ancient court music is also referred to as "classical

music", however there is a distinct difference from

the classical literati music discussed here. The court

music was made by "professional musicians" whose

lives and careers very much depended on the personal interest

of their patrons, the emperors. Those musicians (many

of whom were great masters in history and made great contributions

to the music culture of China) were appointed as music

officers of the court, and had a certain degree of privilege

in society but never enjoyed the same freedom as the scholars

who played music but were not relying on it for a living.

The court music was often performed in ensembles or even

big orchestras, often in association with dance and ceremonial

performances (whereas the classical literati music discussed

here was mainly played solo, and associated with private

occasions). The concept of the concert hall in the present

sense did not exist before the end of the last dynasty

(beginning of the last century). Public places for music

making were often associated with tea houses, restaurants

etc. Classical types of music were often performed in

private settings such as palaces or private houses.

Ancient court music is also referred to as "classical

music", however there is a distinct difference from

the classical literati music discussed here. The court

music was made by "professional musicians" whose

lives and careers very much depended on the personal interest

of their patrons, the emperors. Those musicians (many

of whom were great masters in history and made great contributions

to the music culture of China) were appointed as music

officers of the court, and had a certain degree of privilege

in society but never enjoyed the same freedom as the scholars

who played music but were not relying on it for a living.

The court music was often performed in ensembles or even

big orchestras, often in association with dance and ceremonial

performances (whereas the classical literati music discussed

here was mainly played solo, and associated with private

occasions). The concept of the concert hall in the present

sense did not exist before the end of the last dynasty

(beginning of the last century). Public places for music

making were often associated with tea houses, restaurants

etc. Classical types of music were often performed in

private settings such as palaces or private houses.  The

most miserable were the "professional musicians"

in the entertainment industry, where musicians were either

courtesans or slaves (who could be sold by the owner,

or presented as gift), and therefore among the lowest

social status. It is inconceivable how it came that people

enjoyed their arts, but not show respect to the performing

artists (the situation was somewhat similar in Europe

before the renaissance); indeed it was a shame in human

history! In fact, even business people were considered

among the lowest in social status (which was one of the

important factors that prevented China from developing

fast economically in the past; so was also the fate with

music development!). An example of this can be found in

the famous Tang Dynasty poet Bai Juyi's "pipa

song"

(772-846 AD) describing a courtesan he met during his

exile: The

most miserable were the "professional musicians"

in the entertainment industry, where musicians were either

courtesans or slaves (who could be sold by the owner,

or presented as gift), and therefore among the lowest

social status. It is inconceivable how it came that people

enjoyed their arts, but not show respect to the performing

artists (the situation was somewhat similar in Europe

before the renaissance); indeed it was a shame in human

history! In fact, even business people were considered

among the lowest in social status (which was one of the

important factors that prevented China from developing

fast economically in the past; so was also the fate with

music development!). An example of this can be found in

the famous Tang Dynasty poet Bai Juyi's "pipa

song"

(772-846 AD) describing a courtesan he met during his

exile:

"....

For every song she received endless bolts of silk.

She sang, she beat time, all through the day,

She danced till her head gear fell to the floor.

Wine spilled, skirts stained,

Delicacies rivaled gaieties.

Day after day, and joy upon joy,

Her best years slipped away.

Then her brother joined the army, and her aunt died.

Times changed, and her beauty faded.

Her patrons wandered off, went elsewhere,

And the carriages at her door got fewer and fewer,

Till finally she had to lower herself to

marry a tea dealer ..."

With

the establishment of People's Republic of China in 1949,

the 1950s may be considered the best period for traditional

classical music in China. This type of music could then

reach the general public through radios, records, and

live performances of master musicians who were sponsored

by the government. The attitude of the society toward

performing artists has dramatically changed ever since.

Masters of classical music no longer consider it a shame

to perform in public and make a living from live performance.

They were proud to be "people's artists" and

to perform for the people. Indeed, there seemed to be

a revival of traditional music before the disastrous movement

of the "Cultural Revolution". The destruction

of the traditional values and the spiritual side of the

traditional music through the overwhelming propaganda

of the "revolutionary" ideology during the Cultural

Revolution (1966-76) has led to several consequences as

far as music playing is concerned, particularly for those

who grew up during that pathetic period. For instance,

one of the most obvious consequences is that the pursuit

for spiritual elevation has quite often been replaced

by the pursuit for technical perfection (often narrowly

understood as the ability for fast and precise playing).

Needless to say, masterpieces from the traditional repertoire

require more than just technique to deliver in a way to

touch the soul of listeners; even the techniques for some

traditional pieces might be superficially regarded as

being too "simple" to be of interest by some

players, particularly for those who consider music making

as "show-business". Therefore, "If

the audience is not moved by the music, particularly if

it is a masterpiece from the guqin core repertoire, it

is usually the player's fault and not the listener's",

so said Prof. Li Xiangting, internationally-renowned Chinese

guqin master. This is very true for the masterpieces for

all kinds of traditional instruments. With

the establishment of People's Republic of China in 1949,

the 1950s may be considered the best period for traditional

classical music in China. This type of music could then

reach the general public through radios, records, and

live performances of master musicians who were sponsored

by the government. The attitude of the society toward

performing artists has dramatically changed ever since.

Masters of classical music no longer consider it a shame

to perform in public and make a living from live performance.

They were proud to be "people's artists" and

to perform for the people. Indeed, there seemed to be

a revival of traditional music before the disastrous movement

of the "Cultural Revolution". The destruction

of the traditional values and the spiritual side of the

traditional music through the overwhelming propaganda

of the "revolutionary" ideology during the Cultural

Revolution (1966-76) has led to several consequences as

far as music playing is concerned, particularly for those

who grew up during that pathetic period. For instance,

one of the most obvious consequences is that the pursuit

for spiritual elevation has quite often been replaced

by the pursuit for technical perfection (often narrowly

understood as the ability for fast and precise playing).

Needless to say, masterpieces from the traditional repertoire

require more than just technique to deliver in a way to

touch the soul of listeners; even the techniques for some

traditional pieces might be superficially regarded as

being too "simple" to be of interest by some

players, particularly for those who consider music making

as "show-business". Therefore, "If

the audience is not moved by the music, particularly if

it is a masterpiece from the guqin core repertoire, it

is usually the player's fault and not the listener's",

so said Prof. Li Xiangting, internationally-renowned Chinese

guqin master. This is very true for the masterpieces for

all kinds of traditional instruments.

|

©2008 Philmultic (All rights reserved).

|

A

good performer

can create such a link so that the listeners can experience the power

and the beauty of the music in a way like enjoying a beautiful poem

and painting. To achieve this, only the perfection

of playing technique is not enough. One has to undertand the spirit

of the music, and pass that spirit to the listeners. The best result

can be achieved with the purest heart one can keep. That is, one must

free the mind, and be humble such that the performer becomes the instrument.

In this sense, the live performance is a dynamical and heart-to-heart

process.

A

good performer

can create such a link so that the listeners can experience the power

and the beauty of the music in a way like enjoying a beautiful poem

and painting. To achieve this, only the perfection

of playing technique is not enough. One has to undertand the spirit

of the music, and pass that spirit to the listeners. The best result

can be achieved with the purest heart one can keep. That is, one must

free the mind, and be humble such that the performer becomes the instrument.

In this sense, the live performance is a dynamical and heart-to-heart

process.